Get Eggs-cited for Bird Breeding!

Tawny frogmouths, Victoria crested pigeons, Cinereous vultures. What do these species have in common other than being amazing birds that also happen to live here at the Zoo? They each have their own Species Survival Plan®! This program is run by the Association for Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), and oversees and manages species’ population in zoos by pairing individuals and monitoring breeding to maximize genetic diversity and long-term sustainability of populations. In the SSP, individuals are paired together and Keepers follow specific guidelines to ensure successful breeding, however even in perfect conditions, it can take multiple attempts for the animals to successfully breed.

When it comes to breeding birds, the timing and conditions have to be precisely right for an egg to be fertilized. Once an egg is laid it must be successfully incubated, sometimes for only a couple of weeks or sometimes for several months, during which time it will be exposed to the elements, changes in temperature and/or humidity or positioning, as well as potential predators or the occasional misplaced foot when the parents switch on and off the nest. If the egg survives the incubation process, it still must undertake the gargantuan task of hatching, which can happen as quickly as a couple hours or as long as several days. It is an exhausting process that the chick must complete largely on its own. It is a long process to get from egg to a successful hatch, but the reward is so worth it.

After an egg is first laid staff inspect the egg to make sure it’s in good condition. Are there any defects? Does the Zoo Keeper see any cracks or dents in the shell? Sometimes staff leave the egg with the parents, but other times the egg is pulled for artificial incubation to monitor growth and development.

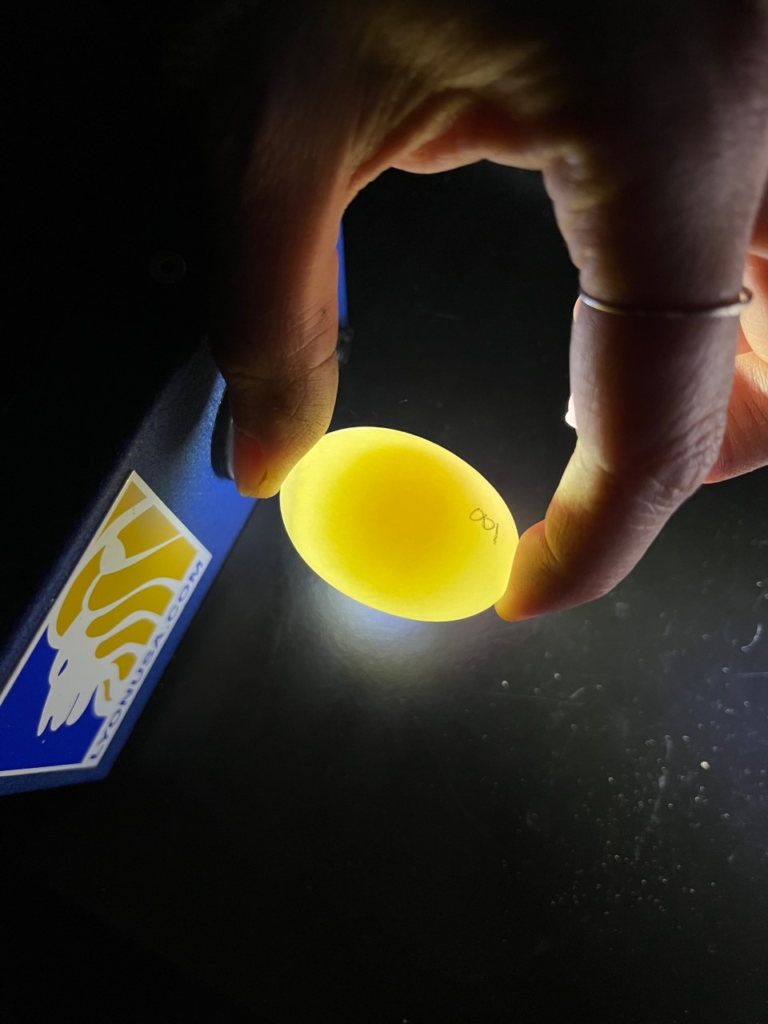

During the first seven to ten days, most eggs begin to show some changes in the yolk if the egg is fertilized. These changes can easily be monitored by shining a light on the egg shell, which illuminates the inside contents of the egg and does not harm the development of the embryo, which is called “candling”. Staff must be very delicate when handling the eggs for measurements and “candling”. In the beginning, an egg should be candled “clear” meaning no visible development is noted. As each day progresses you may start to see subtle changes in the consistency, size, color and/or movement of the yolk. Any of these things can point to a potential chick on the way, but what we are most excited to see in the developing egg is the confirmed presence of an embryo, complete with a network of vessels and a beating heart. This, along with the shape of the embryo, can tell us fairly definitively that if all goes smoothly, a chick is likely to hatch at the end of incubation!

The first picture above is what a fertilized and developing egg looks like during the candling process. The picture below is of an egg laid by the Zoo’s Tawny frogmouth pair. The egg was unfortunately unfertilized and did not develop into a chick, but Keepers are optimistic to see a chick hatch from this pair, and hopefully many of the Zoo’s other bird pairs, in the future!

Thanks to Assistant Curator of Birds Alex Rowland for the insightful information!